There’s an unmistakable whiff of the Wilson era surrounding the EU referendum. Then, as now, the referendum followed a ‘renegotiation’ of the UK’s terms of membership, and the whole thing was basically to allow the Prime Minister of the day to paper over the fissures in his own party, though the Opposition was also split on the issue and we witnessed the spectacle of left-wing Labour stalwarts (this, by the way, was also around the time Anthony Wedgwood-Benn morphed into Tony Benn) campaigning on the same side as right-wing Tories.

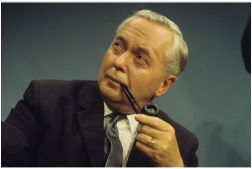

It was Harold Wilson who first convinced me that joining the ‘Common Market’ (not yet the EU) was a Good Thing. A teenager, I had importantly proclaimed myself a Socialist by then and felt terribly affronted when everyone implied Harold Wilson was slimy, even though some of the people who said it were (or rather had been) in his own Cabinet. We think of Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair as having had a bad press, but Harold Wilson was probably the first modern Prime Minister to have such venom directed at him from all sides, and unlike Margaret Thatcher later he seemed to have few admirers to help redress the balance. In my eyes that made him something of an underdog, and I felt so sorry for him I even sent him a Christmas card once.

Anyway, when he made his bid for Britain to join the Common Market in the late Sixties I was right behind him, and was sure that now we had such a nice man as Prime Minister, President de Gaulle would not veto the idea as he had in the early Sixties when Harold MacMillan had tried to join. But of course, de Gaulle wasn’t having any of it this time either.

Thanks to the voting age having just been reduced to 18, I was able to vote Labour in the June 1970 general election, though Labour lost. I went to University in Norwich later that year and instantly joined the Labour Party. My Advisor, Patricia Hollis (now Baroness Hollis) was a Labour Councillor and I campaigned for Labour in the council elections the following year.

It was Edward Heath, after de Gaulle’s demise, who finally negotiated the UK’s entry. But was Harold Wilson pleased? Labour was totally split about joining, so he kept going on about supporting entry only if the terms were right, though there was something about the way he said it that suggested any terms negotiated by Edward Heath never would be right. When entry was secured, opinion polls soon showed a majority against membership (prices had gone up after entry) and many in the Labour Party (led by Tony Ben and Barbara Castle) started talking about a referendum to leave. In the second 1974 election Wilson promised a referendum (although he had earlier said that referendums weren’t the way we did things in Britain) and now he was in power again Wilson himself reverted to being more pro-European. In the event the two-thirds majority against membership (if opinion polls were to be believed) became a two-thirds majority in favour.

My hero’s opportunistic behaviour came as a blow to me, though in truth there were other factors that were making me fall out of love with Labour by the mid Seventies. My ideals are still the same as that teenage Socialist in the Sixties and early Seventies, but you see, it’s everyone else who has changed, not me! My underlying principle remains that the stronger should not harm the weaker. I’ve voted Labour, Liberal, Social Democrat and Conservative in my time, not really with a great deal of conviction, and usually I was voting against a party more than for one. Only once, when a non-mainstream party was standing in the constituency where I lived, have I left the polling booth with the feeling that I had done exactly the right thing. On one level it was a wasted vote, but for me it was a liberation to be able to vote absolutely with my conscience.

It was Harold Wilson who first convinced me that joining the ‘Common Market’ (not yet the EU) was a Good Thing. A teenager, I had importantly proclaimed myself a Socialist by then and felt terribly affronted when everyone implied Harold Wilson was slimy, even though some of the people who said it were (or rather had been) in his own Cabinet. We think of Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair as having had a bad press, but Harold Wilson was probably the first modern Prime Minister to have such venom directed at him from all sides, and unlike Margaret Thatcher later he seemed to have few admirers to help redress the balance. In my eyes that made him something of an underdog, and I felt so sorry for him I even sent him a Christmas card once.

Anyway, when he made his bid for Britain to join the Common Market in the late Sixties I was right behind him, and was sure that now we had such a nice man as Prime Minister, President de Gaulle would not veto the idea as he had in the early Sixties when Harold MacMillan had tried to join. But of course, de Gaulle wasn’t having any of it this time either.

Thanks to the voting age having just been reduced to 18, I was able to vote Labour in the June 1970 general election, though Labour lost. I went to University in Norwich later that year and instantly joined the Labour Party. My Advisor, Patricia Hollis (now Baroness Hollis) was a Labour Councillor and I campaigned for Labour in the council elections the following year.

It was Edward Heath, after de Gaulle’s demise, who finally negotiated the UK’s entry. But was Harold Wilson pleased? Labour was totally split about joining, so he kept going on about supporting entry only if the terms were right, though there was something about the way he said it that suggested any terms negotiated by Edward Heath never would be right. When entry was secured, opinion polls soon showed a majority against membership (prices had gone up after entry) and many in the Labour Party (led by Tony Ben and Barbara Castle) started talking about a referendum to leave. In the second 1974 election Wilson promised a referendum (although he had earlier said that referendums weren’t the way we did things in Britain) and now he was in power again Wilson himself reverted to being more pro-European. In the event the two-thirds majority against membership (if opinion polls were to be believed) became a two-thirds majority in favour.

My hero’s opportunistic behaviour came as a blow to me, though in truth there were other factors that were making me fall out of love with Labour by the mid Seventies. My ideals are still the same as that teenage Socialist in the Sixties and early Seventies, but you see, it’s everyone else who has changed, not me! My underlying principle remains that the stronger should not harm the weaker. I’ve voted Labour, Liberal, Social Democrat and Conservative in my time, not really with a great deal of conviction, and usually I was voting against a party more than for one. Only once, when a non-mainstream party was standing in the constituency where I lived, have I left the polling booth with the feeling that I had done exactly the right thing. On one level it was a wasted vote, but for me it was a liberation to be able to vote absolutely with my conscience.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed