When I was in my early to mid-teens and had been told it was my bedtime, I often spent an hour or more listening to the radio. Nothing unusual in that, but whereas most people of my age favoured Radio Luxemburg (there was little pop music on the BBC then, except on request programmes), I was more interested in the English-language broadcasts that came from Eastern Europe. I had an advantage over some of my peers in that the former family wireless (a solid 1940s Philips thing), had by then ascended to my bedroom. It had long, medium and short wave, though it was the short wave that was of most interest to me. Thus on the same wireless on which Lord Haw-Haw may once have relayed the views of his masters, I was able to listen to his successors doing much the same thing. Perhaps it was not quite the same, as the newsreaders were Russian, East German and so on, but their guests were often Communists, Trade Unionists and sometimes Labour Left comrades enjoying a ‘fraternal visit’ to one or other of the ‘socialist’ countries, whose glories they extolled as arranged.

Although I considered myself a socialist at that time (in a fair’s fair rather than a Marxist sort of way) I was largely immune to the propaganda because even at that age I knew too many people who had suffered at the hands of the Soviet Union. Our neighbours (who became close friends of my parents’) were Poles who had been among those deported to Siberia during the Nazi-Soviet Pact period, and some of my school friends’ parents had suffered the same fate. This was not a coincidence as most Catholic schools in London at that time had quite a few Polish pupils, and most of their parents had come via Siberia (Stalin had agreed to let the survivors go when he was most in need of Churchill’s assistance, though many did not survive their time there or the trek to freedom).

The propaganda from Radio Moscow and its little brothers and sisters in East Berlin, Prague, et al was predictable enough, but what fascinated me was the vocabulary used. When talking about the war, for example, the Nazis were never called Nazis, but Fascists. But the Fascists had been an Italian party which, although similar in some ways to the Nazis, had not been as ghastly: there had been no mass rounding up and deportation of Jews, for example, until the Germans occupied northern Italy. So why had Soviet propaganda given them a name which, on the face of it, was a lesser evil? I guessed that it was partly to do with the fact that Nazi was short for National Socialist, which could be seen as an uncomfortably apt description of the regimes Stalin had set up in his part of Eastern and Central Europe after World War II, complete with antisemitism. There was obviously some sort of house style established in Moscow that others had to follow, because all the ‘Socialist’ countries’ broadcasters used this terminology and, more surprising, so did some of the fraternal guests from the West. These guests, like their hosts, also used other buzz words a lot. ‘Progressive’ was very popular, as in ‘the progressive people of the world look to the Soviet Union to maintain peace in the face of the reactionary American industrial-military complex.’ And, of course, there was ‘Zionism’, the campaign against which was to see half of Poland’s remaining Jews sacked, dispossessed and expelled.

Then, almost out of the blue, one Eastern bloc country started talking normally. The news was read in a balanced way, guests spoke about the good and the bad, the merits of greater democracy and the removal of censorship was were discussed. The Prague Spring had arrived. At the time I was thrilled by the idea of this liberal socialist experiment. It only lasted a few months before the Soviets invaded to put a stop to it all, but I vividly remember the continued broadcasts from Radio Prague after the invasion, initially from a van outside the capital. What is often forgotten now is just how long it took the Soviets to reassert control. Dubcek’s more liberal regime was forced to compromise, but for a while it seemed as though the Russians might compromise too. Radio Prague could not openly criticize the Russians, but they could quote those who did. But gradually the Soviet stooges were back in place and the old language restored. We knew that when words like ‘fascist’, ‘Zionist’ and ‘progressive’ (as in people who supported the Soviet Union) returned, and again ‘fraternal delegations’ from abroad came to praise the building of socialism as defined by the Soviet Central Committee and Arthur Scargill.

Fast forward three or four years to my student days and my trips to Poland. The first was just a holiday with a friend, albeit to an unusual location in those days except for those with relatives there, but my Polish friends’ stories had made me curious. While there I was asked by someone if I could send an ‘invitation’ to someone else on a grapevine. These official ‘invitations’ (you were given a form by the embassy in London), required you to undertake to house and feed the invitees, and to make sure they returned home on the specified date. In practice they expected no such thing. They just wanted to work in England for the summer, and usually had other contacts to help with this. Some, of course, never returned, though if they had received a higher education their relatives back home or some other guarantor were obliged to reimburse the state.

In the event I sent several invitations in the coming years to the lady in question (sometimes she stayed with me, sometimes with others on her grapevine) and to others of her acquaintance, and in return I was invited to Poland, more particularly to Lodz. On my initial couple of visits I got to know some friends and neighbours of hers. She and her father broadly followed the Party line, though this may have been for show, as I was told by others that he had been a member but had fallen foul of the Party some time before. I have to be careful not to offend here, but I think it's fair to say that he was indifferent at best to the recent expulsion of the Jews, in fact the 'anti-Zionist' campaign had its origins in Lodz. The irony was that he lived in the part of the city that had been the wartime Jewish ghetto, from which more than 200,000 had been transported to their deaths less than thirty years before. Not that anyone ever mentioned it.

Others had different views, at least when I was alone with them. A friend of hers I met in town gave a totally different take on things, and the neighbours across the landing invited me in for a drink and a chat on several occasions. The father had been in Auschwitz and later Mauthausen concentration camps, and had been liberated by the Americans. We had some extremely interesting conversations and I once asked him about the use of ‘Fascist’ for Nazi and he laughed. During the German occupation, he said, everyone referred to them as Nazis when not simply calling them Germans. The ‘Fascist’ usage was a Soviet Communist thing. My experience bore that out. Throughout the Seventies and Eighties those who described the Nazis as Fascists were usually on the far left, plus a few trade union leaders. Those ‘fraternal visits’ to the ‘Socialist countries’ had obviously left them with the jargon. And as we know, Fascist is a handy catch-all word to shout at opponents. Official Polish publications did use another word for them occasionally: ‘Hitlerite’. That at least has an accurate feel about it.

And now those words so beloved in the Soviet era are back in fashion. As well as Fascist and Zionist, that old Stalinist faithful ‘progressive’ has re-emerged. ‘Progressive alliances’ had helped the Communists seize power in the post war era, and those who entered the alliance with them were soon dumped (or worse) when they had served their purpose.

The trouble with ‘progressive’ (and it's opposite 'reactionary') is that it’s shapeless, a nonsense word beloved by totalitarian regimes because it can mean whatever you want it to. Are the capitalist companies that created the internet and other modern technology progressive? I doubt if those on the Left would admit that, even while they are using the internet and their smartphones to spread their message. On the other hand, is a self-proclaimed socialist who has never actually produced anything progressive? I suspect he or she would think so. Probably the most telling use of the word was back in the late Seventies when I lived in East London. An Australian junkie whom I had very unwisely put up for three months (after he had initially asked me if I could just put him up for a night) was telling me about a trip to Sweden where, after spending all his money, he went to the Social Services who, as well as finding him a hostel for a night or two, gave him some packets of cigarettes. ‘It really is a progressive country.’ he enthused. So that was his definition of ‘progressive’: free cigarettes for junkies.

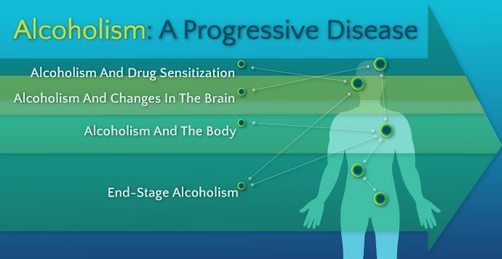

And even outside politics ‘progressive’ can mean something evil as well as good. Some cancers and other nasty medical conditions are progressive too.

Although I considered myself a socialist at that time (in a fair’s fair rather than a Marxist sort of way) I was largely immune to the propaganda because even at that age I knew too many people who had suffered at the hands of the Soviet Union. Our neighbours (who became close friends of my parents’) were Poles who had been among those deported to Siberia during the Nazi-Soviet Pact period, and some of my school friends’ parents had suffered the same fate. This was not a coincidence as most Catholic schools in London at that time had quite a few Polish pupils, and most of their parents had come via Siberia (Stalin had agreed to let the survivors go when he was most in need of Churchill’s assistance, though many did not survive their time there or the trek to freedom).

The propaganda from Radio Moscow and its little brothers and sisters in East Berlin, Prague, et al was predictable enough, but what fascinated me was the vocabulary used. When talking about the war, for example, the Nazis were never called Nazis, but Fascists. But the Fascists had been an Italian party which, although similar in some ways to the Nazis, had not been as ghastly: there had been no mass rounding up and deportation of Jews, for example, until the Germans occupied northern Italy. So why had Soviet propaganda given them a name which, on the face of it, was a lesser evil? I guessed that it was partly to do with the fact that Nazi was short for National Socialist, which could be seen as an uncomfortably apt description of the regimes Stalin had set up in his part of Eastern and Central Europe after World War II, complete with antisemitism. There was obviously some sort of house style established in Moscow that others had to follow, because all the ‘Socialist’ countries’ broadcasters used this terminology and, more surprising, so did some of the fraternal guests from the West. These guests, like their hosts, also used other buzz words a lot. ‘Progressive’ was very popular, as in ‘the progressive people of the world look to the Soviet Union to maintain peace in the face of the reactionary American industrial-military complex.’ And, of course, there was ‘Zionism’, the campaign against which was to see half of Poland’s remaining Jews sacked, dispossessed and expelled.

Then, almost out of the blue, one Eastern bloc country started talking normally. The news was read in a balanced way, guests spoke about the good and the bad, the merits of greater democracy and the removal of censorship was were discussed. The Prague Spring had arrived. At the time I was thrilled by the idea of this liberal socialist experiment. It only lasted a few months before the Soviets invaded to put a stop to it all, but I vividly remember the continued broadcasts from Radio Prague after the invasion, initially from a van outside the capital. What is often forgotten now is just how long it took the Soviets to reassert control. Dubcek’s more liberal regime was forced to compromise, but for a while it seemed as though the Russians might compromise too. Radio Prague could not openly criticize the Russians, but they could quote those who did. But gradually the Soviet stooges were back in place and the old language restored. We knew that when words like ‘fascist’, ‘Zionist’ and ‘progressive’ (as in people who supported the Soviet Union) returned, and again ‘fraternal delegations’ from abroad came to praise the building of socialism as defined by the Soviet Central Committee and Arthur Scargill.

Fast forward three or four years to my student days and my trips to Poland. The first was just a holiday with a friend, albeit to an unusual location in those days except for those with relatives there, but my Polish friends’ stories had made me curious. While there I was asked by someone if I could send an ‘invitation’ to someone else on a grapevine. These official ‘invitations’ (you were given a form by the embassy in London), required you to undertake to house and feed the invitees, and to make sure they returned home on the specified date. In practice they expected no such thing. They just wanted to work in England for the summer, and usually had other contacts to help with this. Some, of course, never returned, though if they had received a higher education their relatives back home or some other guarantor were obliged to reimburse the state.

In the event I sent several invitations in the coming years to the lady in question (sometimes she stayed with me, sometimes with others on her grapevine) and to others of her acquaintance, and in return I was invited to Poland, more particularly to Lodz. On my initial couple of visits I got to know some friends and neighbours of hers. She and her father broadly followed the Party line, though this may have been for show, as I was told by others that he had been a member but had fallen foul of the Party some time before. I have to be careful not to offend here, but I think it's fair to say that he was indifferent at best to the recent expulsion of the Jews, in fact the 'anti-Zionist' campaign had its origins in Lodz. The irony was that he lived in the part of the city that had been the wartime Jewish ghetto, from which more than 200,000 had been transported to their deaths less than thirty years before. Not that anyone ever mentioned it.

Others had different views, at least when I was alone with them. A friend of hers I met in town gave a totally different take on things, and the neighbours across the landing invited me in for a drink and a chat on several occasions. The father had been in Auschwitz and later Mauthausen concentration camps, and had been liberated by the Americans. We had some extremely interesting conversations and I once asked him about the use of ‘Fascist’ for Nazi and he laughed. During the German occupation, he said, everyone referred to them as Nazis when not simply calling them Germans. The ‘Fascist’ usage was a Soviet Communist thing. My experience bore that out. Throughout the Seventies and Eighties those who described the Nazis as Fascists were usually on the far left, plus a few trade union leaders. Those ‘fraternal visits’ to the ‘Socialist countries’ had obviously left them with the jargon. And as we know, Fascist is a handy catch-all word to shout at opponents. Official Polish publications did use another word for them occasionally: ‘Hitlerite’. That at least has an accurate feel about it.

And now those words so beloved in the Soviet era are back in fashion. As well as Fascist and Zionist, that old Stalinist faithful ‘progressive’ has re-emerged. ‘Progressive alliances’ had helped the Communists seize power in the post war era, and those who entered the alliance with them were soon dumped (or worse) when they had served their purpose.

The trouble with ‘progressive’ (and it's opposite 'reactionary') is that it’s shapeless, a nonsense word beloved by totalitarian regimes because it can mean whatever you want it to. Are the capitalist companies that created the internet and other modern technology progressive? I doubt if those on the Left would admit that, even while they are using the internet and their smartphones to spread their message. On the other hand, is a self-proclaimed socialist who has never actually produced anything progressive? I suspect he or she would think so. Probably the most telling use of the word was back in the late Seventies when I lived in East London. An Australian junkie whom I had very unwisely put up for three months (after he had initially asked me if I could just put him up for a night) was telling me about a trip to Sweden where, after spending all his money, he went to the Social Services who, as well as finding him a hostel for a night or two, gave him some packets of cigarettes. ‘It really is a progressive country.’ he enthused. So that was his definition of ‘progressive’: free cigarettes for junkies.

And even outside politics ‘progressive’ can mean something evil as well as good. Some cancers and other nasty medical conditions are progressive too.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed