When I heard that Mother Theresa had called a snap election, or rather had asked Parliament to agree to one, I instantly calculated that this meant an election around the middle of May (no pun intended). Then I heard them say the 8th June, over seven weeks hence. Seven weeks? That's no snap election. An unexpected one, maybe, but 'unexpected' and 'snap' are not the same thing.

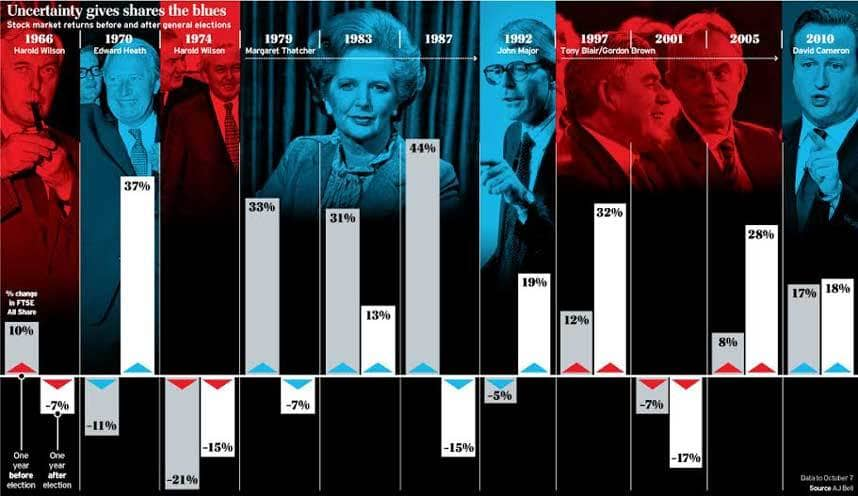

You see, I'm old enough to remember real snap elections, when the 'snap' part was not only about the suddenness of it, but also indicated a relatively short campaign. Not that campaigns were ever that long, with usually around four and a half weeks between the announcement of the election and polling day. This was about what it took to wind up the business of the old Parliament and allow three or four weeks of proper campaigning. The first snap election I recall was in 1970, when Harold Wilson called one earlier than he had to after he saw that opinion polls were favourable (of course, he denied at the time that this was the reason, but published memoirs and diaries of his Cabinet colleagues told a different story). There were 31 days between announcement and election, and the campaign proper did not start until parliamentary and other business was out of the way. . The next 'snap' election was the very next one, which Edward Heath called in February 1974 during the miner's strike (one of several in the 70s and 80s) on a 'who governs Britain?' ticket. Like Wilson's snap election in 1970, it backfired on the one who called it. Not until 2010 did a campaign last as long as five full weeks, and by 2015 it was six. Now we have seven, double what it would have been 25+ years ago.

I presume the lengthening of election campaigns is directly related to the way the modern media operates, with perhaps some contagion from the US, where campaigning is ludicrously long (but they have primaries and all sorts of showbiz frippery). If the extra time added anything to the sum of what we learn about the parties' policies it might be justified, but I'm not sure it does. Either way, I still contend that this is no snap election, and the media pundits who call it that appear to me a bit wet behind the ears and unaware of relatively recent History. Seven weeks is an incredibly long time in politics with enormous potential for gaffes and banana skins. If politicians can't put their case in that time they should be in another job (though most of them should be anyway).

There will, of course, be fibs and misleading generalisations, but what has surprised me most over the years is how some of the same ones are resurrected election after election. Someone on the Labour side, for example, is bound to say something along the lines that we owe our health service to Labour. The truth is that the National Health Service and other aspects of the welfare state originated in the report of an all-party committee, led by William Beveridge, a Liberal. Both the Labour and Conservative manifestoes in the 1945 election duly promised a health service free at the point of delivery. There were differences in how the service would be run (Labour was for the de facto nationalisation of hospitals and GP practices, while the Conservatives talked of working with and financing existing local trusts), but there was total consensus about the 'free at the point of delivery' part. Labour won the 1945 election and so were able to deliver. Yet watch out for the hoary old chestnut from some Labour stalwart about it being Labour's health service which the Tories fought against tooth and nail. On the other side, watch out for the oh-so patriotic stuff from the Conservatives. And, of course, this is the Brexit election, which will almost certainly mean that it will break all records for hyperbole and nonsense.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed