Love's young dream they were not..

Love's young dream they were not.. Transferring novels and short stories to stage and screen can be a risky business even for those who are attempting to be faithful to the original. For longer novels such as War and Peace, Les Misérables and Middlemarch, the main difficulty is usually centred on how to condense them without losing too much. There will always scope for criticism of how the dramatists went about this. For short stories, however, the problem can be is reversed, and it becomes more a question of how much can be added while maintaining the spirit and intention of the author.

Witness for the Prosecution was first published in the early 1920s and would take up around twenty-five pages in a standard paperback. The story is simply told, and as in all whodunnits (though this could be more accurately described as a did-he-do-it) the answer does not come until the end, in this case the very last couple of words. At the centre of the story is young Leonard Vole (we are told he is thirty-three), accused of murdering Emily French, an elderly lady forty years his senior who had befriended him. Mr Mayherne is the solicitor who is called in to defend him. After initial doubts, Mayherne becomes convinced of the young man’s innocence. Vole tells Mayherne that Romaine, his devoted wife, will confirm that he was at home with her when the murder took place. After initially appearing to agree that he was at home, Romaine turns against her husband (though by then it has been revealed that they were not legally married as Romaine has a husband in an asylum in Austria). It seems that she cannot forgive him for his infidelities, and not only refuses to back up his story, she becomes a witness for the prosecution.

Mayherne is devastated, as the case against Leonard Vole now seems overwhelming. Emily’s maid, Janet McKenzie, swears he was in the house at around the time of the murder, and now Romaine asserts that he arrived home a little later with blood on his shirt. What’s more, the maid insists Leonard knew that Emily had written a will leaving almost everything to him, a knowledge Leonard denies. Then, during the course of the trial, Mayherne receives a mysterious note telling him to visit an address in the East End where he will learn something about Romaine Vole. Although doubtful, he keeps the appointment in the dark, squalid room. The wretched, drunk, scarred woman he sees there offers to sell him letters written by Romaine to ‘Max’, her secret lover. In the letters she reveals her plan to lie about Leonard not being at home when he said he was, and in effect frame him for the murder. The trial resumes and Mayherne produces the letters while questioning her. Faced with them, she breaks down and admits she wrote the letters and that Leonard was with her at the time of the murder. He is found not guilty, while she must expect a jail term for perjury.

Some time later Mayherne meets Romaine by chance. She reminds him she was an actress and reveals that she had been the old hag from whom he had purchased the letters, imitating her voice to prove it. She explains that nobody would have believed her, Leonard's lover, if she said he was at home, which is why she became a witness for the prosecution so that she could then be discredited. Her time in jail was worth it if it meant she could save his life. Here is how the story ends.

‘I still think,’ said little Mr Mayherne in an aggravated manner, ‘that we could have got him off by the – er – normal procedure.’

‘I dared not risk it. You see, you thought he was innocent – ‘

‘And you knew it? I see.’

‘My dear Mr Mayherne,’ said Romaine, ‘you do not see at all. I knew - he was guilty.’

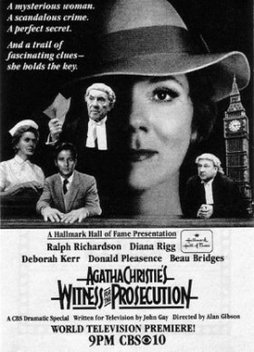

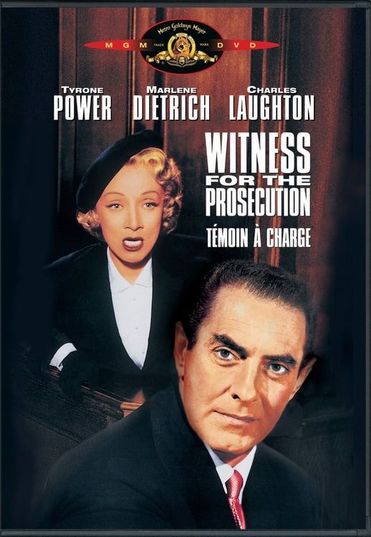

There have been several dramatizations, the most famous being the 1957 film (base on the West End Play of 1952) starring Tyrone Power, Marlene Dietrich and, as the barrister, Charles Laughton. In 1982 another film was made starring Beau Bridges, Diana Rigg and Ralph Richardson, though the script was broadly the same as the 1957 one. The play and the two films derived from it have some minor alterations, though at the end there is a significant addition. After the trial is over and the public have left the court, the barrister encounters Mrs Vole (not called Romaine here) who tells him of her trick. As they are speaking Leonard enters, followed by a young woman who kisses him ostentatiously. It transpires she is his lover. In a fit of Dietrich-style rage Mrs Vole seizes the dagger that had been an exhibit in the trial (though in the original story the victim had been bludgeoned to death) and stabs him in the stomach. He obligingly dies instantly. ‘She didn’t murder him, she executed him,’ proclaims Charles Laughton, and begins to prepare the case for her defence. It seems that in the Fifties a murderer could not be seen to have got away with it.

The play and films also make Mayherne a Barrister rather than a solicitor, and give him a different name, though as a tilt to the original there is a Mr Mayhew in the team. In their quest for famous actors the films also age Mr and Mrs Vole. Tyrone Power and Marlene Dietrich were well past their thirties, in fact poor Power was almost literally at death’s door, dying the following year.

The most recent version was made by the BBC for its 2016 Christmas Agatha Christie drama. In terms of accuracy it starts well. It reverts to the original early Twenties period, Romaine gets her proper name back (though Mayherne becomes Mayhew, which looks like change for change’s sake), and the Voles are young again (sorry, Marlene). But then it starts to go in a different direction and the additions and alterations come thick and fast. Not only do the Voles get younger, so does the victim, and the old lady in her seventies becomes a middle-aged good-time gal. There are some hints of the original story: according to Christie, Emily had eight cats, and one is included here (and a very significant part it plays), though the fortune for which Emily is murdered is much enhanced. According to Christie she lived fairly frugally in Cricklewood, whereas here she lives riotously in Holland Park and leaves enough for the Voles to spend the rest of their days in swanky hotels, and that after they had given a cut to Mayhew. The First World War and the young men sacrificed in it were mentioned in the original story, but here those couple of sentences are turned into a whole new co-plot, as Mayhew’s wife cannot forgive him for coming home from the war while their son did not. In the original story he had a dry cough, whereas here he never stops coughing, a condition brought on by poison gas in the trenches.

The biggest deviation of all, however, must be the arrest and execution of the hapless maid, Janet McKenzie, who was assumed to be the murderer after Leonard was acquitted. It was Mayhew who pressed the case against her, and his reputation and wealth was much increased by his supposed genius. Later he is astonished to meet the just married Voles in a seaside hotel in France, where they reveal the truth about the evidence given at Leonard’s trial. This means that not only did a guilty man go free (as in the original) but an innocent woman was hanged. (This twist is more than an added bit of macabre entertainment, as it alters Romaine's character. Christie's Romaine had been hopelessly in love with a wrong'un, but not wicked.) Another blow awaits Mayhew, as his wife makes clear that she never will forgive him for their lost son and can never be intimate with him. And so the stage is set for yet another tragedy, and the original punchline of that twenty-five page story is buried even deeper.

My request to future dramatists is not to try to fit stories into a specified time slot regardless of their length. The consequent additions or subtractions can only destroy the original story and turn it into something never intended by the author. But then, I suppose it's ultimately all about bums on settees.