...Or rather her creation, William Brown (or 'Just William' as some people called him, though in fact that was simply the title of the first book in the series). I say 'her' but, in common with many of her readers, I was not aware for some time that she was female. The name Richmal didn't help. To me it conjured up a schoolmaster, complete with the scholastic gown many of our teachers wore in my all-boys grammar school. I was also surprised, when I discovered the truth, that a woman should have had such an insight into the working of boys' minds, especially as she had never had children of her own and had been a teacher in an all-girls school.

The William series were not the first books I had read, of course, nor the first to capture my imagination. In primary school I had been familiar with other characters such as Worzel Gummidge and a host of children's books popular at the time. As it was a Catholic school I was also encouraged to read a series known as 'Vision Books' about saints and missionaries in different eras, not all of them as dry as you might imagine, though all of them extolled the virtues of martyrdom or at least self-sacrifice and they did not steer clear of sticky ends: we were familiar not only with Thomas More's demise on the block but also with Edmund Campion's more lingering hanging, drawing and quartering. It goes without saying that our view of Elizabeth I's reign was very different from that of our Protestant friends. Another book that stands out from those early years was Ian Serraillier's The Silver Sword about three children who escape from their home in Warsaw when their parents are being arrested by the Germans. We actually acted out a few scenes from that, and one of my first theatrical lines, aged about eight, was 'Open in the name of the Gestapo!' (eat your heart out, Herr Flick!).

Yet all these early forays into literature were quickly forgotten when I discovered William. It started during my first few weeks at grammar school when I began reading the books on the bus to school (or rather two buses each way, as it was a long journey from Stoke Newington to Highgate). My friend, Les (still a friend to this day), the only one in my year who had to make the same journey, was also a fan, and he piqued my interest by telling me the plots of the stories I had not read. It helped that William was our age, wore a similar school uniform, also hated Latin (though he did not appear to have been caned as I was for failing to conjugate verbs properly), sometimes had ham-fisted schemes to make the world a better place and, above all, was surrounded by a cast of eccentric adults.

There were also some differences. The first books of the series were written in the 1920s, and William and his friends were from a fairly wealthy background. During the course of the series (the last books were written in the 1960s, and Richmal Crompton died in 1969) his family actually become less obviously wealthy. In the 1920s they had a cook, a maid (maybe more than one) and a gardener, all of whom offer William occasion for sport. By the Second World War they appear to have dwindled to a housekeeper and by the sixties there are no servants in evidence at all. This is, of course, a reflection of the social changes that occurred during the early and mid twentieth century. Throughout it all William remains about eleven, and his long-suffering parents do not age, nor his elder brother and sister, Robert and Ethel, both of whose comic and usually disastrous amorous pursuits drive some of the plots along. There are also a series of eccentric adults who come in and out of the stories. Mad majors, fake clairvoyants, potty writers and pretentious avant-garde artists are brought down to earth and occasionally helped by William. These characters, along with the writing style, sometimes give the books a surprisingly adult feel, and certainly many adults have been tickled by them. For example, is it a coincidence that the vegetarian group who move briefly into the village in the 1930s are led by an old duffer who bears a remarkable resemblance to George Bernard Shaw?

The most famous eccentrics in the series are probably the Botts, a Cockney couple who had once run a corner shop and who became rich after they accidently created a delicious sauce which became a commercial success. They move into the Hall, the largest house in the village, and Mrs Bott is acutely aware that, despite her wealth and philanthropic endeavours, the neighbours look down on her. It is their seven-year-old daughter, Violet Elizabeth, who gives William and his gang ('the Outlaws') the most grief. She is always intruding into their macho pursuits and famously threatens to 'thcream and thcream and thcream till I'm thick' unless they obey her commands. It is fortuitous that Violet Elizabeth was created by a woman: a man would probably not have got away with it. And yet there is another girl, Joan, whom William likes very much. For all practical purposes she is part of the gang and actually rescues William from a couple of scrapes.

For me the most important thing about the William books was that they made me want to write. They were an introduction to intelligent fiction, the bridge between children's and adult literature. Today, alas, they are more intelligent than some 'adult' fiction.

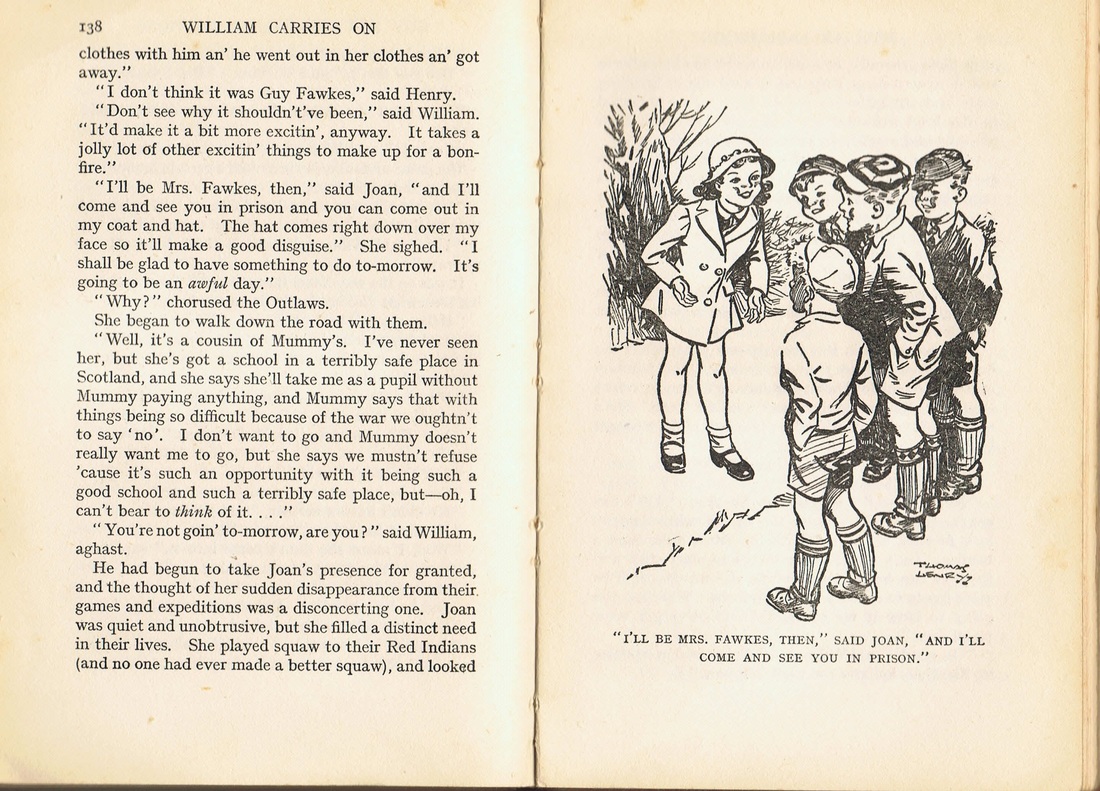

The reproduction below is from one of the books written in World War II. With invasion likely and air-raids a fact of daily life, it looks as though Joan is going to be sent away to a school in a safer part of the country. What can William do about it?

The illustration is by Thomas Henry, who created the pictures for all but the last few of the books. The visual image of William and the other characters was shaped by him as much as by Richmal Crompton. Strangely, they only met once, and that very briefly.

The William series were not the first books I had read, of course, nor the first to capture my imagination. In primary school I had been familiar with other characters such as Worzel Gummidge and a host of children's books popular at the time. As it was a Catholic school I was also encouraged to read a series known as 'Vision Books' about saints and missionaries in different eras, not all of them as dry as you might imagine, though all of them extolled the virtues of martyrdom or at least self-sacrifice and they did not steer clear of sticky ends: we were familiar not only with Thomas More's demise on the block but also with Edmund Campion's more lingering hanging, drawing and quartering. It goes without saying that our view of Elizabeth I's reign was very different from that of our Protestant friends. Another book that stands out from those early years was Ian Serraillier's The Silver Sword about three children who escape from their home in Warsaw when their parents are being arrested by the Germans. We actually acted out a few scenes from that, and one of my first theatrical lines, aged about eight, was 'Open in the name of the Gestapo!' (eat your heart out, Herr Flick!).

Yet all these early forays into literature were quickly forgotten when I discovered William. It started during my first few weeks at grammar school when I began reading the books on the bus to school (or rather two buses each way, as it was a long journey from Stoke Newington to Highgate). My friend, Les (still a friend to this day), the only one in my year who had to make the same journey, was also a fan, and he piqued my interest by telling me the plots of the stories I had not read. It helped that William was our age, wore a similar school uniform, also hated Latin (though he did not appear to have been caned as I was for failing to conjugate verbs properly), sometimes had ham-fisted schemes to make the world a better place and, above all, was surrounded by a cast of eccentric adults.

There were also some differences. The first books of the series were written in the 1920s, and William and his friends were from a fairly wealthy background. During the course of the series (the last books were written in the 1960s, and Richmal Crompton died in 1969) his family actually become less obviously wealthy. In the 1920s they had a cook, a maid (maybe more than one) and a gardener, all of whom offer William occasion for sport. By the Second World War they appear to have dwindled to a housekeeper and by the sixties there are no servants in evidence at all. This is, of course, a reflection of the social changes that occurred during the early and mid twentieth century. Throughout it all William remains about eleven, and his long-suffering parents do not age, nor his elder brother and sister, Robert and Ethel, both of whose comic and usually disastrous amorous pursuits drive some of the plots along. There are also a series of eccentric adults who come in and out of the stories. Mad majors, fake clairvoyants, potty writers and pretentious avant-garde artists are brought down to earth and occasionally helped by William. These characters, along with the writing style, sometimes give the books a surprisingly adult feel, and certainly many adults have been tickled by them. For example, is it a coincidence that the vegetarian group who move briefly into the village in the 1930s are led by an old duffer who bears a remarkable resemblance to George Bernard Shaw?

The most famous eccentrics in the series are probably the Botts, a Cockney couple who had once run a corner shop and who became rich after they accidently created a delicious sauce which became a commercial success. They move into the Hall, the largest house in the village, and Mrs Bott is acutely aware that, despite her wealth and philanthropic endeavours, the neighbours look down on her. It is their seven-year-old daughter, Violet Elizabeth, who gives William and his gang ('the Outlaws') the most grief. She is always intruding into their macho pursuits and famously threatens to 'thcream and thcream and thcream till I'm thick' unless they obey her commands. It is fortuitous that Violet Elizabeth was created by a woman: a man would probably not have got away with it. And yet there is another girl, Joan, whom William likes very much. For all practical purposes she is part of the gang and actually rescues William from a couple of scrapes.

For me the most important thing about the William books was that they made me want to write. They were an introduction to intelligent fiction, the bridge between children's and adult literature. Today, alas, they are more intelligent than some 'adult' fiction.

The reproduction below is from one of the books written in World War II. With invasion likely and air-raids a fact of daily life, it looks as though Joan is going to be sent away to a school in a safer part of the country. What can William do about it?

The illustration is by Thomas Henry, who created the pictures for all but the last few of the books. The visual image of William and the other characters was shaped by him as much as by Richmal Crompton. Strangely, they only met once, and that very briefly.